Buy open, buy fast: how open contracting helped Lithuania’s Coronavirus response

Lithuania’s institutions were struggling to procure life-saving protective equipment in the early months of the pandemic, so the Public Procurement Office (PPO) launched a comprehensive analysis of its emergency contracts. It identified an increasing number of untested suppliers, overpriced protective equipment, and risky high-value direct awards. To build legitimacy and trust for the management of the pandemic response, PPO decided to fully open the details of more than €80 million in emergency contracts to the public through a dedicated portal. The move allowed the government, civil society and journalists to investigate spending and solve problems. Based on this success, Lithuania is now moving to put open data and open government at the heart of its new procurement reforms.

Like everyone else, Lithuania saw soaring demand for PPE and medical equipment as the pandemic hit in March last year. As a small country at the shores of the Baltic Sea, the Lithuanian government knew they would struggle to compete for critical and scarce supplies on the global market. But it still took many people by surprise to see the levels of fraud and misrepresentation that the country’s authorities had to tackle. In one case, investigative journalists Miglė Krancevičiūtė and Šarūnas Černiauskas, working for media outfit Siena, uncovered a suspicious shipment of 30,000 Chinese masks called ‘Love Surprise’ at the port city of Klaipėda in Lithuania. The company sending them was just a couple of months old and their certificates were fake. A criminal investigation followed.

Open it to fix it

Lithuania’s governmental Public Procurement Office (PPO) knew it had to do something to maintain the trust of the public. They had simplified their procurement negotiations procedures during the emergency to conclude contracts for PPE quicker, but speeding up the process also meant putting aside the usual checks-and-balances that maintain accountability. Buyers shifted to direct awards without publishing the details of the tenders, so critical information on purchases only became available once the contract was signed (and published)

Lithuania’s central e-procurement system (CPP-IS, the Central Public Procurement Information System) was cutting edge when it was introduced in 2008 and, since 2016, included a publicly accessible contract register. But when the pandemic hit, its document-based system struggled to keep up with the emergency response. Critical information could not be analyzed easily.

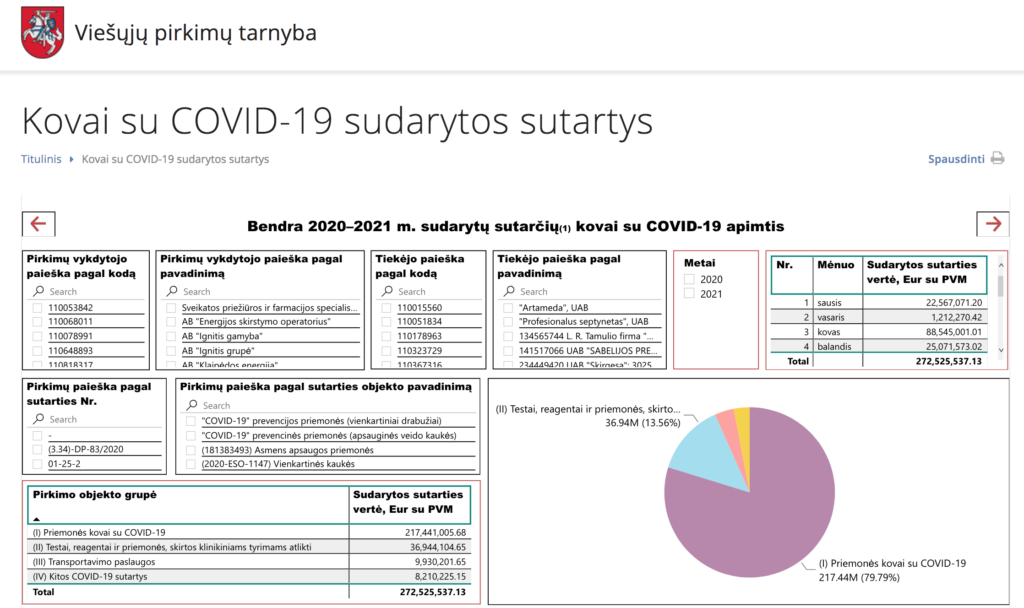

With an influx of untested suppliers and high-value contracts awarded during the pandemic, the PPO conducted a comprehensive emergency procurement review in June 2020, collating and publishing 1,214 COVID-19 contracts for PPE, disinfectant and logistics from January to May 2020. Recognizing the value of CSO and journalist monitoring, it shared all the information as open data on a publicly accessible dashboard. The dashboard offered user-friendly visualizations of key pandemic procurement information to show who brought what, from whom, and when.

The analysis revealed the government had spent a total €84.4 million on PPE and other supplies. The top 10 contracts accounted for almost half of the value of all contracts awarded (49%) and 45% of the total went to just two foreign suppliers.

“Open data helped raise certain red flags, such as the need to diversify the supply chain,” says Laura Kuoraité, senior advisor at Methodical Assistance Division at the PPO. “It also re-informed what we’ve been saying for years: how important it is to educate our public buyers, to show the importance of proper planning, and knowing your market.”

“We noticed new types of suppliers such as those that did not act in the field before, for example, a company that sells festive decorations started selling PPE. That’s quite unusual. It creates difficulties because you’re dealing with a supplier that could be delivering successfully, but you’re just not sure given the short timeframe in which you have to act.”

OCP’s Karolis Granickas, himself a concerned Lithuanian citizen, was impressed: “The PPO genuinely wanted to understand how the government had performed in the first wave of procurement. They faced some obvious challenges, such as what to do with suppliers you have never heard of but who came up with a good bid. People had to make very hard decisions on the spot. The PPO’s goal was to shed light on these decisions to learn lessons going forward. Sharing the data was a way of enlisting the help from civil society, journalists, and others to fill in the picture and help during a moment of crisis”

Increased scrutiny by civil society and journalists

As Sergejus Muravjovas, CEO of Transparency International Lithuania explains: “COVID-19 is a stress-test for any anti-corruption system. The publication of the open data allowed us for the first time ever to dig deeper and truly understand ‘what it is we know,’ and ‘what it is we don’t know.’

Sergejus and his team, supported by a small grant from OCP, started digging into the data as well as sending Freedom of Information requests to the 10 largest contracting authorities and to five major COVID-19 patient treatment hospitals (for a total of 12 procurers, as there was some overlap).

TI Lithuania asked the contracting authorities to submit all additional COVID-19 procurement contracts, including for personal protective equipment, medical equipment dedicated to the fight against COVID-19, and testing kits, if not already published by the PPO.

In total, 136 additional COVID-19-related contracts signed with 73 different suppliers that were not initially disclosed were submitted to TI Lithuania. The total value of these contracts was €7.98 million, adding another 10% of government’s Covid spending total. TI Lithuania’s ability to source additional data showed some of the limitations of the procurement office’s oversight authority and the information was duly added to the country’s procurement dashboards.

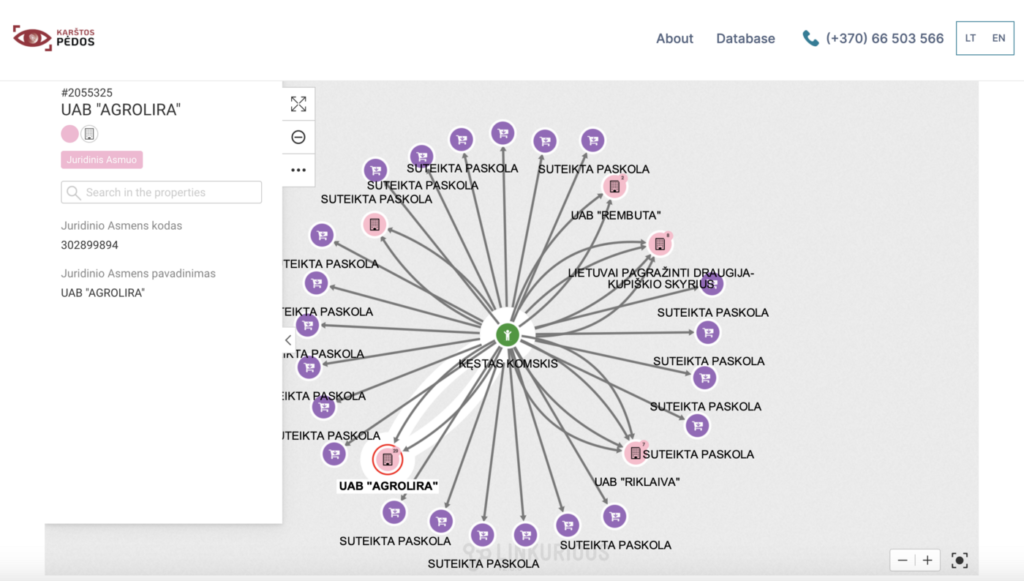

The PPO also collaborated with investigative journalism agency Siena fresh from their ‘Love Surprise’ mask investigation. Siena, in collaboration with Media4Change, created a tool that analyzes links between government agencies, public contracts and politically exposed persons (called Karstos Pédos or “hot feet”) after Šarūnas Černiauskas, Siena’s founder, got frustrated with hours spent digging through Lithuania’s various procurement databases. The new tool changed that: “in a few clicks, you can trace connections on the platform that would take a skilled journalist hours or days to make,” says Černiauskas.

In December 2020, TI Lithuania was able to introduce its study and recommendations to the anti-corruption commission at Parliament, which committed to act on them.

“We hope this leads to amendments in the law and the way we conduct emergency procurement in Lithuania,” says Sergejus. “There is a clear need to centralize public procurement – we have too many different agencies. We also need to digitalize, and it’s clear we need to have better risk management in place. I hope that this report and other similar stories encourage not only civil society but also anti-corruption agencies and the public sector to have a more measured approach to corruption risk management and transparency in general.”

A lasting commitment to reform

Lessons from how transparency and open data helped improve the pandemic response are now being applied to Lithuania’s Covid recovery. The PPO is already collecting more granular data and tagging contracts in recovery packages to allow better tracking of recovery expenditures.

“The economic recovery is probably an even more important conversation than the emergency phase because it’s multidimensional and it will require detailed examination of strategic decisions and the entire implementation chain,” says Sergejus. “There are plenty of risks when you think of the scale of funds now coming our way.”

The PPO is also planning to improve its IT infrastructure to collect more detailed, standardized information across the whole procurement cycle. it will be building a completely new e-procurement system for the country called SAULE IS, which will be fully digital and data-driven, covering public contracts across their lifecycle.

The PPO has committed to implementing the Open Contracting Data Standard as a key part of that shift to streamline the publication of open procurement data, improve analysis and link to other relevant datasets. Agencies such as the Ministry of Environment have also started considering open data approaches to track EU Green New Deal objectives too.

“One of the goals of the future new and digitized SAULE IS is to transform all public procurement processes into smart digital, data-driven solutions in the electronic space,” says Marius Zemaitis, the PPO’s IT Lead. “It will be possible to choose goods and services not only according to their price and quality but also by reduced environmental impact, encouraging a highly-specialized system focused on providing fair, green procurement.”

A new anti-corruption law is under discussion in parliament. “This is a potential gamechanger,” says Sergejus. “The draft contains a lot of the right vocabulary that allocates responsibility not just to the Special Investigation Service (Lithuania’s anti-corruption department), but also heads of departments and institutions in the public and private sectors. It speaks of measurable results and good examples. If it comes to fruition, it will be an enormous step-change.”

Last October, the European Parliament held a hearing on emergency procurement, where OCP emphasized the role of open data and stakeholder engagement – as seen in Lithuania – in safeguarding the emergency procurement response.

In November, the Financial Times recognized the country’s efforts by shortlisting Lithuania for the 2020 Intelligent Business Awards.

A new PPO report investigating the agency’s response in the second wave of the coronavirus is due in April 2021 and will provide further insights into managing emergency procurement using an open and transparent response.

We are excited to follow the next steps in the journey and share the lessons across our community as open contracting champions look to their coronavirus recovery and to cleaner, greener, and smarter procurement.

Cover photo: Czeva (CC BY-SA 4.0)