The great reset for commercial relationships and contracts: why we can’t leave it to the lawyers to address our many global crises

Right now, the world is in crisis – whichever way you look. We have the pandemic, supply chain disruptions, soaring inflation, the war in Ukraine and continued inequalities around race and gender, as well as climate change.

We need to collaborate if we are going to have any chance of tackling any one of these crises, yet alone all of them together. And we cannot collaborate effectively without the highest levels of transparency and openness.

Professor Ugur Sahin, CEO of BioNTech, recognized that we needed a radical shift in how we collaborate at scale to develop a vaccine that would protect people from COVID-19. Speaking at our WorldCC Academic Symposium last year, he appealed to the audience not to rely on traditional approaches to contracting: if he had left it to the lawyers they would have been there for years. Instead, everyone signed a simple 4-page Memorandum of Understanding focused on the objectives of what they were trying to achieve and committing to “the highest levels of transparency – unprecedented information sharing in real time.”

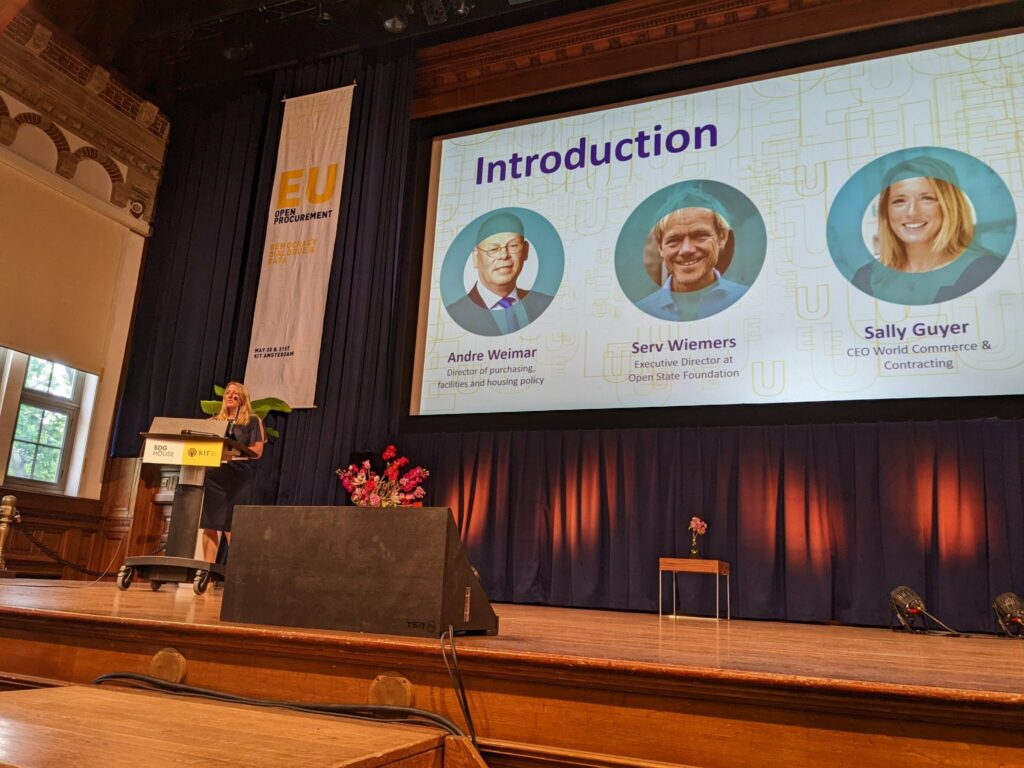

When I asked him whether what he had achieved was repeatable and scalable, he laughed and said: “Of course it should be. Trust-based collaboration should be the norm and not the exception.” It is a challenge that I took to heart as CEO of World Contracting and Commerce.

We talk about “open” and “transparent” but what do we really mean? Let’s be clear about their purpose and their consequences. I see three major reasons for public interest in open contracting.

1) A wish to tackle, expose or avoid corruption.

2) Improve competence, which includes multiple aspects of both public and political interest, such as fairness, good judgement and reflecting national or local interests and policy priorities.

3) Finally, achieve better value, focusing not only whether goals and objectives from a contract were met, but whether they optimized the social return, and how they were adjusted or adapted through active management of a contract and its outcomes.

These factors take us into the realm of relational economics and force a radical departure from past models of evaluation and award which focus too much on compliance and on both parties – government and company – trying to shift risk onto each other. They are a zero-sum game where one party tries to win and the other must lose.

In every case, a key consequence of being open should be to raise public confidence in government – to build trust.

Yet to do this, it is not enough simply to publish contracts. To the extent it enables scrutiny and debate over an award, there is a clear benefit, though that tells us little about competence or value achieved. That is where open contracting can add so much more value: delivering a process that is open to scrutiny from inception of requirement through to completion of performance.

We know from our research that the biggest single factor in loss of value is in the statement and ongoing review of scope and goals. Did we set the right requirements? Did we adequately evaluate all the potential solutions? Did we allow for and monitor change? And based on these factors, did we make the award under an appropriate contracting and reward mechanism?

While questions of competence certainly make media headlines and impact public trust and confidence, I would suggest that what the public cares most deeply about is the delivery of value. Today, with the extent of uncertainty and volatility that surrounds us, value frequently depends on more flexible, adaptable, agile forms of contracting.

We need to move beyond our focus on certainty and fixed forms of risk allocation and budgeting. In too many of our procurement systems, when failure occurs – a massive delay or a huge overspend – it is typically impossible to determine where fault lies. All too often, the process either fails to notice in time or fails to respond to warning signs, so we fail to learn the lessons.

We live in an era of predictable unpredictability; instead of using contracts and contracting policy to try to drive and create certainty – an impossible task – we must use them to help us navigate that inevitable uncertainty. We need the people, the process and the technology to enable this new world.

This is where true openness of data comes to the fore: a level of data transparency that both informs and demands activity throughout the contracting lifecycle, forcing issues and opportunities to be grasped and resolved. Value is not achieved at the time of award, but through the actual performance of a contract. It is a variable that government’s rarely focus on, disconnected between procurement systems covering the planning, tender and award and treasury systems covering payment. To analyse value today, we typically rely on the reactionary function of an audit office.

In a democracy, the audit office acts should act with independence and integrity, exposing not only wrong-doing, but also incompetence and failure to achieve stated goals. While it has full access to documents and people, it is conducting a post-mortem after the event. Here is what we need to fix before things go wrong:

- Accessibility: how accessible is our procurement system and our contracts? Have we designed them with the user in mind? And have we even thought about who that user is?

- Creativity: how adaptive is our procurement system? Not just pre-award but most importantly in the post-award environment as this is where change happens. Do we embrace change? Can we even cope with it?

- Transparency: Do we have appropriate visibility of data throughout the supply and delivery ecosystem? What are the feedback mechanisms and institutional loops through which we act – for the public good – on that data?

As our world grows ever more complex, as our abilities through technology expand, the meaning of open contracting will adapt and change. As we expand our vision beyond corruption to embrace competence and value, we need a far more dynamic and deeper system of real-time monitoring. We must make ‘open’ an incentive to perform, not a stick with which to punish and allocate blame. We must push harder to make ‘open’ a vehicle to encourage and stimulate innovation and change, not a reason for inertia and blind compliance with rules. We must make ‘open’ a system that monitors and measures value throughout the social ecosystem that it serves and that is itself a driver for responsiveness and adaptability.

Many of our 50,000 members at WorldCC are commercial suppliers to governments: they all have their horror stories of seeing boxes ticked at the expense of the bigger picture. They will sign up to openness, as long as it is not a one way street. 88% of our members polled globally expressed hope for increased levels of collaboration and a more ‘fair and reasonable’ approach to contracting as we emerge from the pandemic. They are also optimistic: in that same poll, 74% actually believed new and better ways of working with government and other partners would happen.

The Nobel Prize for Economics in 2016 went to Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmstrom who observed that the world is held together by contracts. Today, the European Commission is evaluating how it can measure the European economy as an ecosystem of contracts. These obscure, mostly unintelligible and inaccessible artefacts, actually lie at the core of human society, binding us together and providing a framework for trust. That is why openness matters. So, as we consider what this truly means, we must be imaginative, we must be creative, and we must be inspired.