Digging into Moldova’s never-ending road with open data

In Moldova, waiting for a road to be repaired can be like watching grass grow, literally. When journalist Olga Ceaglei and her colleagues at the nonprofit media collective RISE Moldova began looking into a project to improve the highway leading from the country’s capital to the Romanian border in 2016, the repairs had been going on for years and appeared to be nowhere near complete. Progress was moving so slowly in some places that weeds, and even grape vines, had sprung up on the construction sites.

They set about determining what was causing the excessive delays. Ceaglei searched for information about the public contract behind project – basic details about the tender, the procuring entity, the amount, the contractor, and any donors – on the state road authority’s website. But this site doesn’t include the actual contracts, so she also filed a Freedom of Information request. Occasionally, authorities reject these requests, Ceaglei says, but she was lucky this time and got the full contract documents.

“We decided to publish it, just to be sure that every citizen from Moldova would have the opportunity to look at this contract,” Ceaglei said. “In my opinion, it’s very, very important that all public contracts should be available online. In Moldova we have experts who can look at the contract to see if there are some [irregularities] there.”

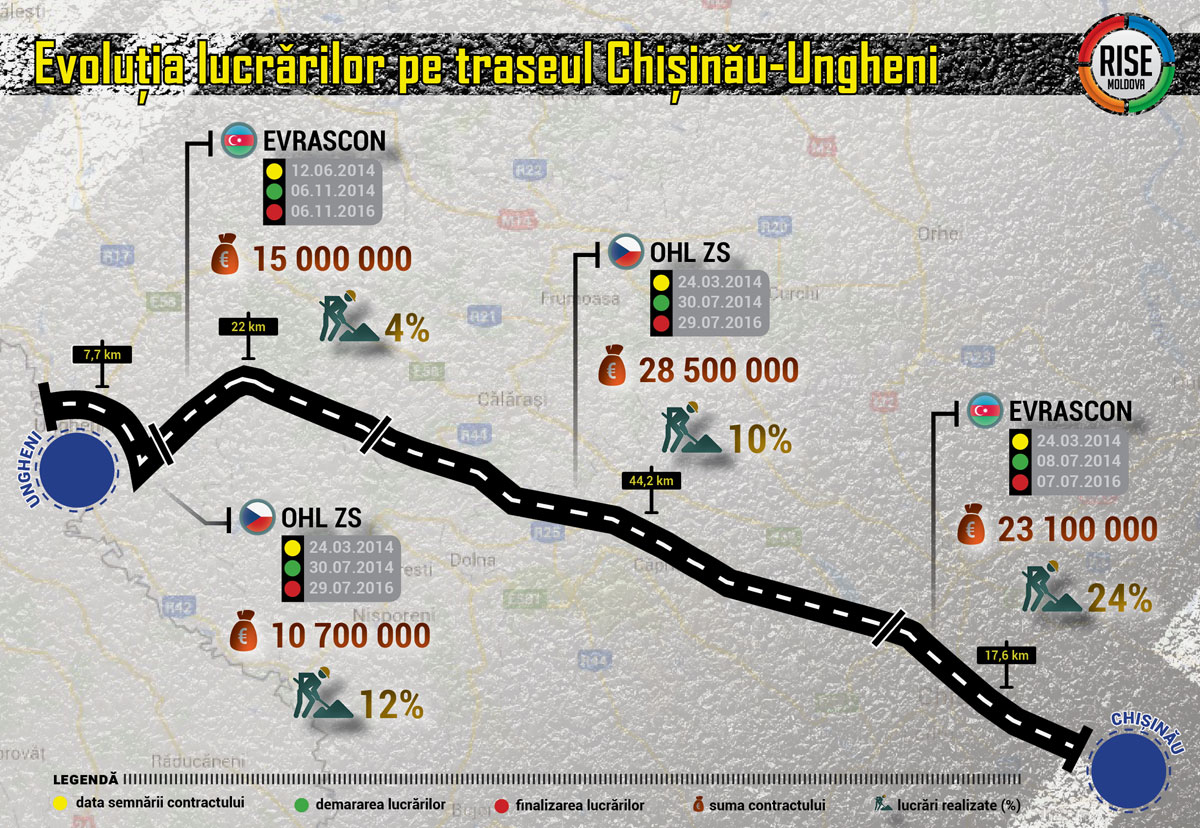

She found that the state road authority had signed two contracts in 2014, with a Czech company and another from Azerbaijan, to repair the 92 kilometer-long stretch of road from Chișinău to the town of Ungheni at the Romanian border. The total value of the contracts was EUR 77 million with funds coming from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the European Investment Bank.

By the end of April 2016, two years after making the deals, both companies had completed less than a quarter of the work. With both contracts due to expire just months later, Ceaglei contacted the relevant parties to find out what was going on.

Ceaglei thinks the contracting process was broken from the beginning. “It’s about standards, the process of authorization, the award system,” she said.

On 2 March, the day before RISE published their story, the transport minister, who is responsible for the state road authority, held a press conference in which he warned the Czech company that if it failed to meet its contractual obligations, it risked damaging its reputation in Moldova and across Europe, and the credibility of the European Union as a donor. While the minister had previously threatened to cancel the contracts, says Ceaglei, it’s actually very difficult to annul such an agreement.

The Azerbaijani company, the minister told her, had financial problems due to delays in receiving payment for other projects they’d done in other countries in the region, and recently, the firm had failed to pay the workers’ wages in Moldova.

On the other hand, representatives from the companies told Ceaglei that they wanted to do the work but the technical specifications and plans of the project kept changing, and they had difficulties in getting approval from government institutions to carry out the work.

“We, as a company with our own equipment, have the opportunity to start the work, but if I do not know exactly what the requirements are, how can I work?” Adrian Vovec from OHL ZS, the Czech company, told RISE Moldova.

“To be honest, I don’t know, maybe both sides have their truth,” Ceaglei said.

The new road is still incomplete, as of summer 2017. It still takes 2.5 hours to drive the full 92 kilometres and the Czech contractor has had to pay sizeable penalties for the delays in finishing the project.

The case serves as an example of why companies should speak up about the issues they encounter when engaging in public procurement, Ceaglei says.

“In my opinion, [companies] should be more open and say, ‘we are a serious company, we have a good reputation, and we want to win this contract [and] do our work in the correct way, but we have this situation because the state institutions are not working well’.”

The story also sparked a public discussion about how taxpayers’ money is spent.

“In general, Moldovan people are very kind and have a lot of patience,” she said. “[In this case] some of them are very angry and they see that for months and years, the roads are being worked on and nothing happens.”

“That’s why this kind of story is important: so that people know who is doing the work.”

RISE Moldova is an award-winning community of journalists, programmers and activists that uses data journalism to investigate corruption and organized crime.

Public procurement reform in Moldova is ongoing with support from the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. An open contracting platform has been built and a modernized e-procurement system is being developed to improve transparency, but engagement from companies and organizations like RISE, as well as willingness from government to collaborate and take action, will make all the difference to ensuring public money is managed efficiently.