ProZorro: How a volunteer project led to nation-wide procurement reform in Ukraine

Picture: Sorry for inconvenience, we are changing the country. ProZorro.

Ukraine’s public procurement sector has long been associated with corruption, with an estimated UAH 50 billion (US$2 billion) lost annually through shady deals and limited competition. And yet, the country is considered a recommended model for e-procurement reform by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and won a prestigious World Procurement Award in May 2016.

How did Ukraine manage such a radical shift within its public procurement system?

This unlikely story begins right after the Revolution of Dignity in March 2014. As the uprising rallied against the corrupt Yanukovych regime, a group of volunteers decided to overhaul one of the most corrupt areas: public procurement.

The cornerstone of the public procurement reform has been an e-procurement system, ProZorro, which was developed in close cooperation between government, private sector, and civil society.

Here’s a brief story of how this development came about, what makes ProZorro so special, and what we can learn for similar reform processes in other countries.

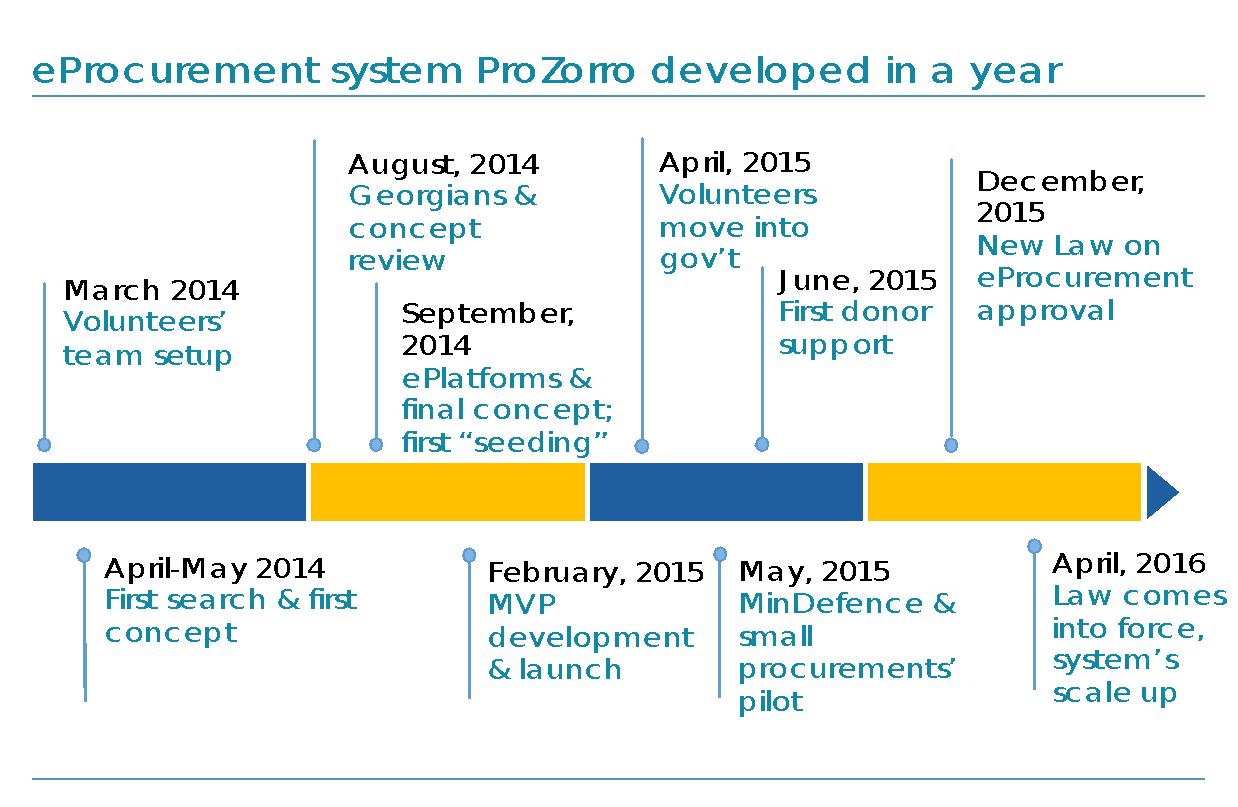

The ProZorro project was initiated in Kiev in May 2014 by a group of anti-corruption social activists. The project was inspired by public procurement reforms in Georgia, with the experience of two e-procurement experts, Tato Urjumelashvili and David Marghania, guiding the development of an electronic procurement system for all Ukrainian public agencies. With the help of commercial platforms, a pilot of the e-procurement system ProZorro was launched in February 2015.

History of e-procurement system ProZorro

In April 2015, the civil servant responsible for supervising Ukraine’s public procurement reform, Deputy Minister of Economic Development and Trade Max Nefyodov, asked a ProZorro coordinator Oleksandr Starodubtsev, to lead the government’s public procurement department, and other volunteers from the project joined shortly after. In the meantime, a strategy for the e-procurement system’s implementation was developed.

By March 2016, more than 3,900 governmental organizations from all over Ukraine had joined the pilot project, and saved more than UAH 1.5 billion (around US$55 million). The purchases were “below-threshold” contracts worth less than UAH 100,000 (UAH 1 million for state-owned enterprises), which means they were not regulated by Ukrainian procurement laws and the volunteers didn’t have to obtain a government licence to carry out the pilot project. Below-threshold tenders account for around half of Ukraine’s entire procurement budget.

Public agencies including defence, police, customs, health, infrastructure and energy, have awarded more than 85,000 tenders through the ProZorro system, as of July 2016.

With the new law into effect in April 2016, the project has been expanding step by step to cover all the country’s procurement. Meanwhile, the central platform, which was hosted by Transparency International Ukraine throughout the development and pilot phase to avoid bureaucratic processes and cut costs, has been transferred to the state and is now available at www.prozorro.gov.ua.

On 1 August, it will become mandatory for all contracting entities to use e-procurement for all purchases, above- and below-threshold.

Other complementary initiatives have also been successfully implemented or tested. A professional risk-management system with “red flag indicators”, a new official web portal, an online course for contracting authorities, and an e-library of typical specifications are innovations that were made possible through open contracting.

In May 2016, Ukraine officially joined the WTO Government Procurement Agreement, which not only opens up the markets of its members – including 28 European nations, the US, Canada, and Japan – to Ukrainian suppliers, but also demonstrates the Ukrainian system’s compliance with international standards.

What is special about ProZorro?

ProZorro, which means “transparently” in Ukrainian, has some specific attributes that make it a novelty in the procurement world. Firstly, everything is open. All information related to the tender process, including suppliers’ offers, can be accessed and monitored by anyone. The system is open source, and all data is structured in line with the Open Contracting Data Standard, making cross-country data comparison and analysis possible.

Secondly, ProZorro is a “hybrid model” e-procurement system, which means the information is stored in one central database, but suppliers and contracting authorities can access the data from a number of different platforms, choosing the one that best serves their needs. Using an API, these interfaces are connected to the central database so that all the information is synchronized across all platforms.

Finally, the key actors in the project play their own, unique role in what we call the “golden triangle of partnership”. Government actors are responsible for setting general rules and protecting information; businesses are responsible for providing services to contracting authorities and suppliers; and civil society is responsible for managing business intelligence modules and developing risk-management methodologies. This style of cooperation has significantly improved trust among all key stakeholders.

The reform approach: Are there any implications not only for Ukraine but also for other countries?

It may sound odd, but reforms very often seem to be associated with the passing of new laws. The changes to Ukraine’s procurement system, however, did not start with a new version of the law on public procurement. They started with a group of people who had one common dream – to make each and every step of the public procurement process transparent and open for monitoring by anyone.

The team shared several common beliefs that guided their approach in an environment where corruption had eroded citizens’ trust in public institutions: that private business, driven by competition, would be much more efficient in providing services than the government, and that civil society would have a genuine interest to monitor public procurement compared to public officials who may harbor ulterior motives.

The project has not been without its setbacks. Two ministers leading the department responsible for procurement resigned during the implementation phase, and while some agencies have welcomed the reform, others captured by vested interests have resisted. The new legislation promises to act as a powerful incentive to those who have been stalling on making real changes. Ukraine’s Prime Minister has even said that the heads of state authorities who fail to transition to the ProZorro system should be dismissed.

The success of ProZorro is a remarkable example of how a small group of individuals from different parts of society have been able to work together to repair a broken system, despite operating in a politically and economically uncertain environment.

We’re now working closely with Moldova’s finance ministry to share our experience in reforming the public procurement sector. But a model like ProZorro has the potential to be adopted by any country struggling with a lack of openness in its public spending. In little over two years, we have made substantial progress toward achieving our shared goal of increasing transparency in tendering, improving access for businesses to government deals, increasing competition among bidders, and reducing corruption risks in our country.